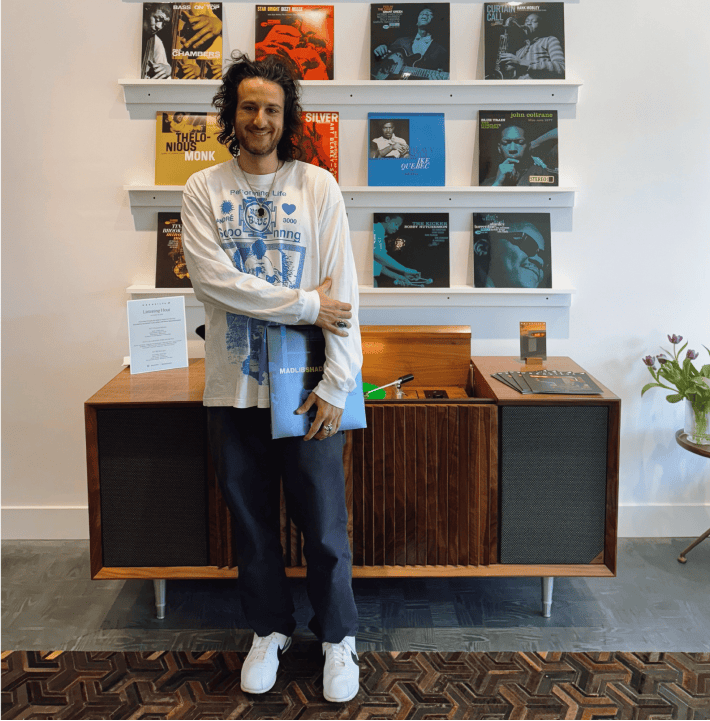

Music writer Jeff Weiss dives into the connections between jazz and hip-hop, exploring the legacy of Blue Note Records and its role in shaping 90s rap.

At ten years old, hip-hop production remained a total enigma to me. I couldn’t figure out what hidden reserve supplied this mystic brew of tectonic-rupturing bass lines, filthy drum fills, and empyrean brass horns. Did live musicians stuff themselves into the recording booths with the rappers? Did the beatmakers play every note themselves like funky red-eyed sorcerers? And wouldn’t these creative tributaries eventually run dry? Commercial rap was barely a decade old. If you didn’t live in New York City, information was still esoteric and hard to access.

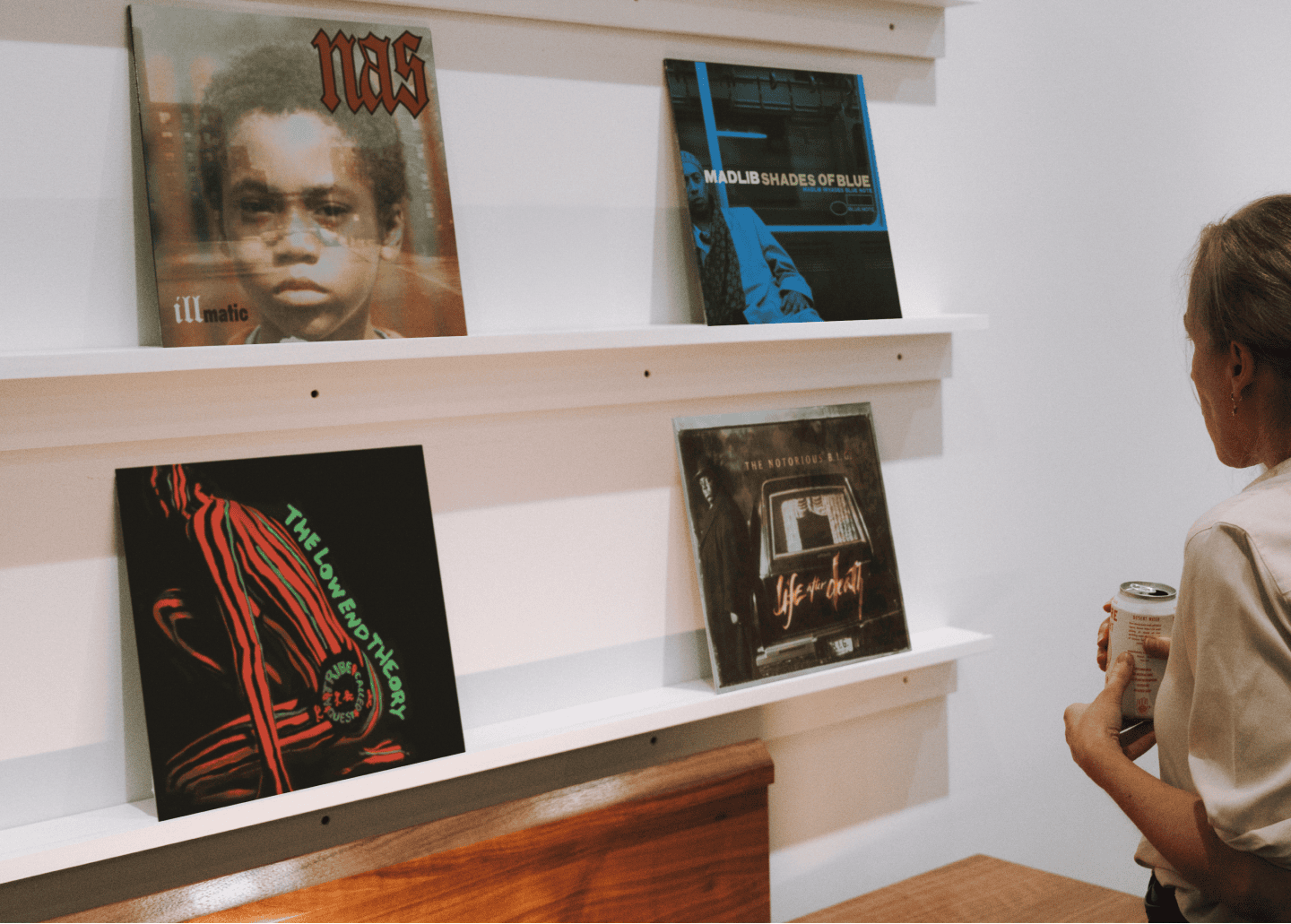

My father told me that it was just a fad – the new version of disco. But on the album that rarely left my CD player, Q-Tip’s father offered a dharmic rejoinder: things move in cycles. To Q-Tip’s dad, hip-hop reminded him of bebop. Or so he was quoted on “Excursions,” the first song and spiritual heartbeat of the ‘90s masterpiece Low End Theory.

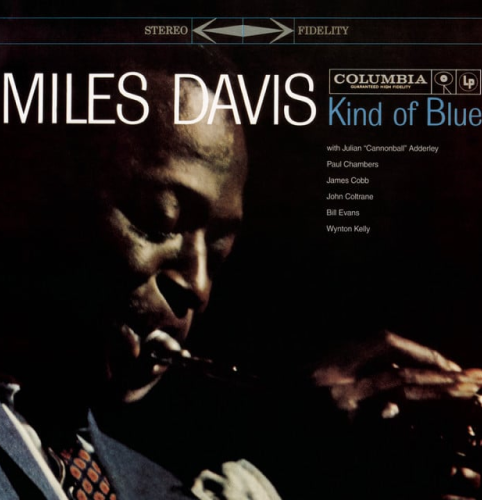

I knew nothing about bebop. Jazz was something that my grandfather listened to in his glassed-off den filled with World War II books, Pacino VHS tapes, and thousands of CDs: Oscar Petersen, Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Count Basie, Dexter Gordon. I’d eventually inherit them all. At the time, it just seemed like the dull music of out-of-touch AARP members.

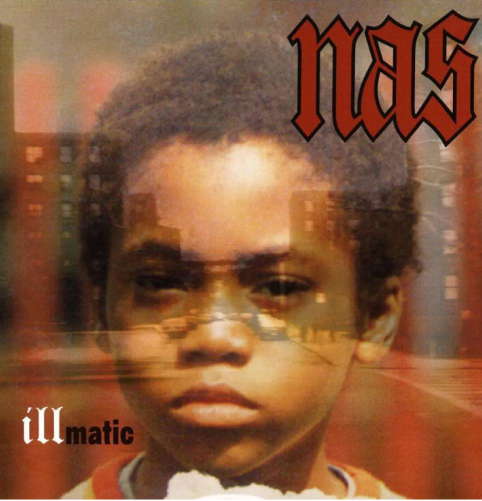

It’s hard to remember when I realized that almost everything I loved was borrowed directly from the past. I eventually learned that hip-hop producers were sampling old records, but never had the budget to seek out the originals. Besides, hip-hop felt so exciting and vibrant that it never occurred to me to dig much deeper than what was on the radio and cable. The G-Funk era led into the glory days of the East Coast underground, and no one bothered to explain to teenagers that Biggie’s sample from “Hypnotize” came from the trumpet player Herb Alpert – who, as it turned out, went to Fairfax High with my grandmother.